Donald Trump’s imposition of a 25% tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico, announced on March 4th, presents one of the most significant challenges to the global trading framework since the Smoot-Hawley tariff of 1930. This recent tariff is not an isolated incident but rather echoes a long historical precedent in American economic policy that has experienced various phases of protectionism. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act is infamous for instigating a trade war that exacerbated the Great Depression and led to the fragmentation of global trade into hostile blocs. Historical accounts from credible sources, such as The Economist, provide clear warnings about the perils associated with protectionist measures.

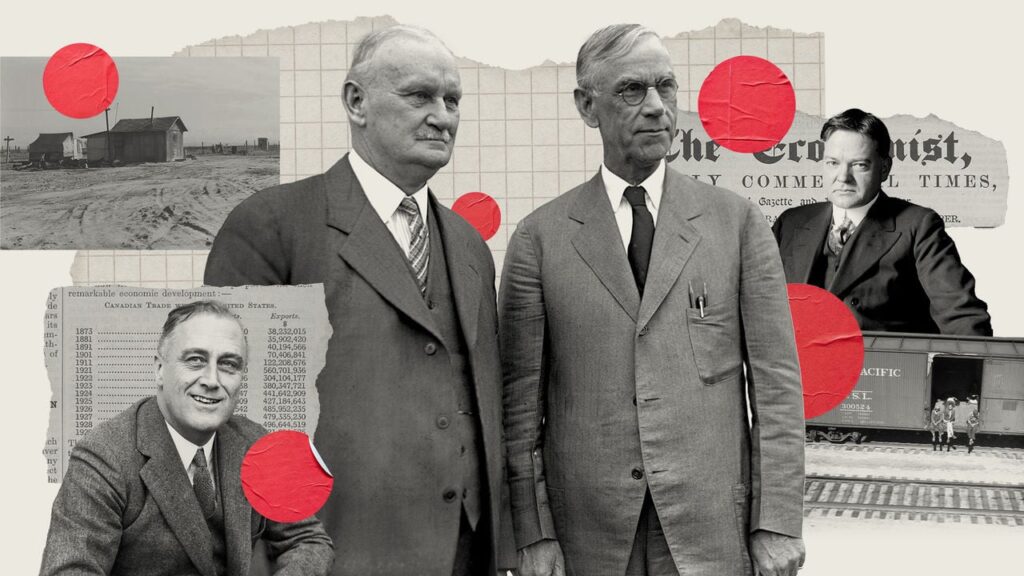

This particular chapter in tariff history starts under President Herbert Hoover, who was elected in 1928. Hoover’s administration aimed to support American agriculture, adversely impacted by the post-World War I recovery in Europe, which brought competitive produce on the market. In 1929, two Republican figures, Senator Reed Smoot from Utah and Congressman Willis Hawley from Oregon, advanced a legislative proposal to increase tariffs specifically on agricultural imports, a move that would significantly impact Canada, the United States’ largest trading partner.

During this heated political climate, it became evident that any adjustment in U.S. tariff policy would pose significant consequences for Canada, given its economic reliance on American trade. Canadian responses to these developments mirrored domestic anxieties, as Canadian leaders and economists monitored the evolving situation with considerable concern. This scrutiny only intensified as the proposed bill languished in Washington, D.C., through a grueling 18-month deliberation period. As the Great Depression deepened, various American industries began lobbying for additional protections, resulting in a wider body of support for the tariff changes. In response, Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King raised tariffs against American goods, while offering reductions for other nations within the British Empire.

Despite substantial objections from over 1,000 American economists and business leaders warning President Hoover against endorsing the bill, he ultimately signed it into law on June 17, 1930. Critics illustrated a dire forecast for the economy following the enactment of the Hawley-Smoot Tariff, describing the legislative process as a tragedy fueled by political interests that overshadowed the initial intention of supporting the agricultural sector. The expectations of farmers pivoted as the bill evolved into a framework that raised nearly 900 duties to an excessive level, illustrating how political influence can distort economic practices.

As anticipated, the fallout from the tariff was significant. The U.S. economy suffered greatly, with global trade shattering under the weight of the economic downturn. Between 1929 and 1932, American exports and imports plummeted by approximately 70%, with the Hawley-Smoot Tariff contributing to this dramatic decline. The increasing unpopularity of prolonged tariff measures led to a shift in Congressional balance after the Democrats took control of the House in early 1931. Disillusionment with high protectionism mounted both within the electorate and among members of Hoover’s Republican Party, a trend that emerged as a significant issue in the 1932 presidential election.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Democratic candidate, accused the Republicans of erecting economic barriers that isolated the United States from vital international markets. He advocated for a policy shift aimed at enhancing trade relations, promoting the notion of negotiation over rigid tariffs. Nevertheless, a consideration remained that even this progressive stance might become susceptible to political compromise as pressure from various domestic interests loomed.

After Hoover’s defeat in November 1932, the political landscape shifted dramatically. Roosevelt secured congressional authority to negotiate tariffs, which signified the beginning of a careful and gradual reduction of trade barriers. The Economist at the time articulated a hope for a robust pivot away from protectionist tendencies, emphasizing that excessive protectionism could become a liability rather than a safeguard.

Ultimately, as history has shown, the broader implications of tariffs such as those enacted by Hoover continue to resonate. Trump’s reversion to protectionist policies may lead to similar complications in today’s context. The lesson from the past stresses the critical importance of trade as a facilitator of economic growth and international cooperation, rather than as an obstacle that hinders prosperity. As society reflects on these themes, it becomes clear that the consequences of tariff imposition may again be borne by consumers, underscoring the urgent need for a reevaluation of isolationist principles in favor of more integrative economic policies.