Recent scientific advances have led to a significant discovery—a fossilized jawbone retrieved from the ocean floor, approximately 15.5 miles (25 kilometers) off the coast of Taiwan, has been identified as belonging to a Denisovan. This groundbreaking finding, which was published in the journal *Science*, arises from meticulous research analyzing the proteins within the teeth attached to the jawbone. Notably, this marks the third confirmed location of Denisovan habitation, expanding our understanding of these ancient humans’ diverse environments across Asia, including Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau.

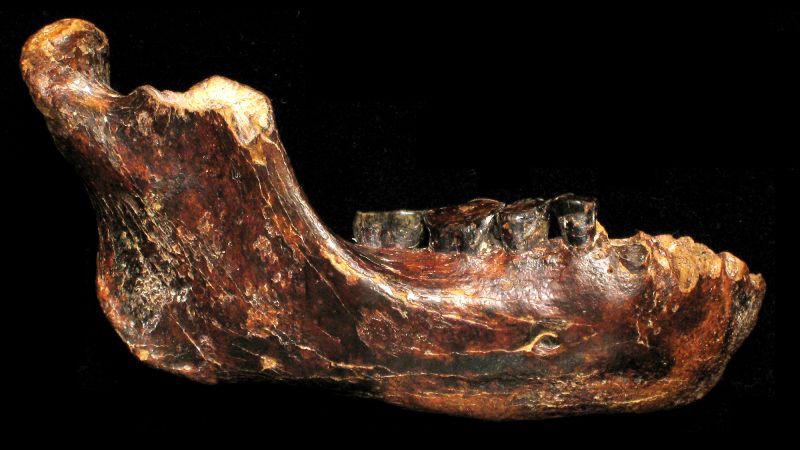

The journey of this discovery commenced over a decade ago when fishermen off Taiwan’s coast began to find various ancient bones in their nets, remnants from a time when sea levels were notably lower, allowing for land connections between regions like Taiwan and China. Among these finds, the jawbone, dubbed “Penghu 1,” caught the attention of scientists due to its unusual features. It wasn’t until recent proteomic techniques were utilized that its true identity emerged. According to Frido Welker, an associate professor at the University of Copenhagen’s Globe Institute, protein preservation has proven to last longer than DNA, making analyses on ancient specimens a viable option, even years after their discovery.

Previously, attempts to categorize the Menghu 1 fossil had left researchers puzzled. It was suggested that the fossil belonged to the genus *Homo*, which includes both contemporary humans—*Homo sapiens*—and other archaic humans like Neanderthals. However, initial DNA recovery attempts were unsuccessful, leaving the species unverified. Through their recent work, scientists have confirmed that the jawbone is indeed from a male Denisovan, as indicated by specific peptide sequences from extracted proteins.

The collaboration was monumental, with Chun-Hsiang Chang, a curator of paleontology at Taiwan’s National Museum of Natural Science, being instrumental in this identification process. After discovering the jawbone and realizing its potential significance, Chang transported it to Copenhagen in hopes of further elucidating its origins. Along the way, he encountered challenges, including airport security apprehensions that momentarily delayed his research efforts. Still, with successful extraction and identification methods, researchers were able to reveal crucial connections to known Denisovan genetic material.

Denisovans, first identified in 2010 from a small finger bone found in Denisova Cave, are regarded as enigmatic due to their mysterious traits and limited fossil record. Research shows that this group, much like Neanderthals, interbred with early modern humans, leaving a genetic legacy that can be traced in contemporary populations across Asia. As subsequent discoveries of Denisovan remains surfaced—from a jawbone in Tibet to a tooth in Laos—the scientific community recognized that these ancient humans thrived in a wider array of environments than initially understood.

The jawbone’s noteworthy preservation is particularly surprising, considering its long-standing stay at the ocean’s bottom. Experts like Zhang Dongju suggest that with the increasing volume of Denisovan fossils being identified and molecular signatures being documented, the prospect of finding and classifying more Denisovan remains seems promising. Katerina Douka, an associate professor in archaeological science, emphasizes the paradox surrounding Denisovans; while genetic information is abundant, morphological data remains sparse—leaving much to be learned about their external qualities and characteristics.

The absence of wisdom teeth in the Penghu 1 mandible evokes further interest in how Denisovans may have differed in physical attributes from modern humans. This aspect, alongside their lacking chin features, paints an intriguing image of the species, suggesting variations between males and females that remain to be studied.

Currently, the Denisovans do not have an officially recognized species name, although some scholars propose calling them *Homo juluensis*, aligning them with other fossil discoveries in China, such as the recently termed “dragon man.” Moving forward, Chang intends to revisit the National Museum of Natural Science’s extensive collection of fossils, applying similar protein extraction methods in hopes of uncovering more treasures that could unravel the mysteries surrounding the Denisovans, enriching our understanding of this remarkable chapter in human evolution.