In a groundbreaking achievement in the field of ancient genetics, researchers have successfully sequenced the entire genome of an ancient Egyptian man, providing remarkable insights into his ancestry that dates back to the era of the first pyramids. This monumental research revelation signifies a major leap in our understanding of the interconnections of ancient civilizations.

The individual under examination was discovered within a sealed clay pot in Nuwayrat, a village located south of Cairo. Experts estimate that he lived approximately 4,500 to 4,800 years ago, making his DNA the oldest ancient Egyptian sample thus far analyzed. The comprehensive study reveals that around 80% of his genetic lineage can be traced to North Africa’s ancient populations, while the remaining 20% is linked to individuals from West Asia and the Mesopotamian region.

Published on a Wednesday in the esteemed journal *Nature*, the findings emerge as new evidence supporting the hypothesis of extensive cultural and trade connections between ancient Egypt and neighboring societies within the Fertile Crescent, an area that encompasses present-day Iraq, Iran, and Jordan. While previous investigations mainly relied on archaeological artifacts to suggest these ties, the present work emphasizes the importance and value of genetic data in understanding the interactions of these ancient peoples.

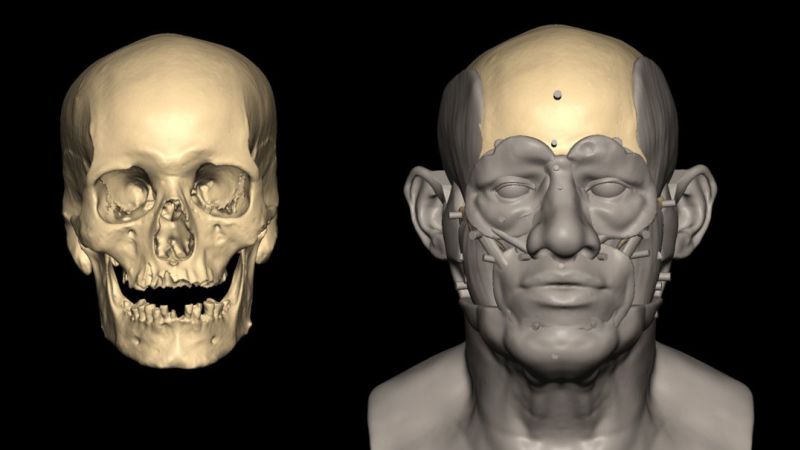

The researchers also conducted a thorough examination of the man’s skeletal remains, leading them to conclude that he had endured significant labor throughout his life. Dr. Adeline Morez Jacobs, the lead author of the study and a visiting research fellow at Liverpool John Moores University in England, remarked that by piecing together various components of the man’s DNA, bones, and teeth, they have been able to sketch a well-rounded portrait of his life. This comprehensive genetic information opens the prospect for further explorations of the migratory patterns that might have influenced the ancestry of ancient Egyptians.

While there has been speculation about ancient trade routes and knowledge exchanges in the region, the hard evidence has often been lacking due to the preservation challenges posed by Egypt’s warm climate. However, the exceptional preservation of the remains uncovered in a clay pot allowed for successful DNA extraction, marking a significant milestone in genetic data retrieval from ancient samples.

Although the research sheds light on a single individual, scientists express hope that future work could provide insights into the origins of the first Egyptians at the very inception of one of history’s longest-lasting civilizations.

Svante Pääbo, a Swedish geneticist who won the Nobel Prize in 2022 for sequencing the Neanderthal genome, had initially attempted to decode DNA from ancient Egyptian remains over 40 years ago. Unfortunately, his efforts were hindered by inadequate DNA preservation, a challenge that persisted until contemporary advancements allowed for the sequencing of this complete genome.

Using a method known as “shotgun sequencing,” the authors of the new research could analyze all DNA molecules isolated from the teeth of the ancient man. This means that future researchers can access the entire genome to procure further insights without needing additional material from the skeletal remains. The burial method, where the individual was not mummified, likely contributed to the remarkable state of his DNA.

Throughout the study, samples taken from the roots of his teeth provided vital information. Analysis indicated that this man spent his childhood in the arid climate of the Nile Valley, consuming a diet rich in wheat, barley, and animal protein—staples consistent with agricultural practices typical of the region.

Notably, while 80% of his ancestry is traced back to North Africa, the identification of links to older genomes from Mesopotamia suggests substantial migration patterns into Egypt. Supports for this notion echo throughout the findings of dental anthropologist Joel Irish, who noted that the skeletal features most closely resembled those found in Western Asian individuals.

A major takeaway from this unique analysis, highlighted by Iosif Lazaridis, a research associate at Harvard University, underscores the genetic diversity of early Egyptians, indicating that they were predominantly North African but exhibited a notable west-of-Mesopotamia influence. This climatic stability, combined with the burial method, played a crucial role in DNA preservation, allowing for extraordinary insights into a civilization founded on intricate cultural ties.

As researchers continue to piece together the complexities of human history, studies such as this underscore the significant contributions that genetic research can make in unraveling the enigmas of our ancestral lineage.