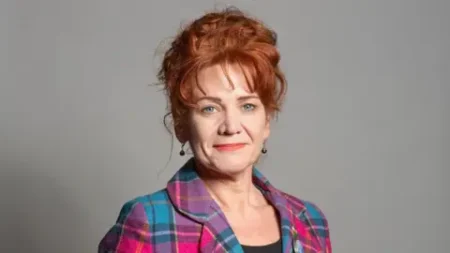

In a recent political discourse surrounding the Labour Party, MP Zarah Sultana made significant comments regarding Jeremy Corbyn’s approach to antisemitism during his leadership. During an interview with the New Left Review, Sultana asserted that Corbyn “capitulated” on the definition of antisemitism, particularly referencing the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) definition, which she argues conflates antisemitism with anti-Zionism. This statement comes amidst her and Corbyn’s recent endeavors to launch a new political party aimed at reenergizing leftist politics and challenging the current government’s policies, particularly regarding their stance on Gaza.

Sultana’s remarks have ignited considerable controversy, particularly among Jewish organizations. Notably, the Board of Deputies of British Jews condemned her comments as “a grave insult”. In response to these criticisms, Sultana expressed her proud anti-Zionist stance on social media, emphasizing a commitment to her beliefs and challenging the media’s portrayal of her views. This declaration aligns with a broader theme of her argument, which situates the media as allies of the establishment rather than guardians of objective truth.

As she reflects on Corbyn’s legacy, Sultana recognizes both the strengths that Corbynism brought to British politics—namely its robust policy platforms and mass appeal—as well as its shortcomings. She articulated that Corbyn had made “a serious mistake” by being overly conciliatory in the face of opposition from both the state and the media, suggesting that the movement needed to assert itself more aggressively. Sultana’s perspective echoes the sentiments of those within the Labour left who feel that the establishment has sought to undermine progressive politics through various forms of censorship and misrepresentation.

The backdrop to these discussions is the Labour Party’s 2018 adoption of the IHRA definition of antisemitism into its code of conduct, a decision that was contentious within the party and was influenced by ongoing tensions regarding the handling of antisemitism complaints during Corbyn’s leadership. Many critics within the left argue that this definition has been wielded as a weapon against critics of Israel, stifling legitimate discourse on Palestinian issues. Sultana contends that the movement under Corbyn was “frightened” and failed to engage adequately with its critics, which culminated in missteps that weakened its position.

The controversy intensified with responses from observers like Alex Hearn, co-director of Labour Against Antisemitism, who criticized Sultana’s assertions by labeling her an “extremist.” Hearn emphasized the necessity for a clear definition of antisemitism to mitigate violence and discrimination against Jewish communities, invoking the historical context of heightened antisemitic incidents during Corbyn’s tenure.

In light of these tensions, Sultana remains adamant in her rebuttals against what she regards as smear campaigns against her and her new party. The ongoing discourse touches on the broader issues of anti-racism, social justice, and the complexities of political identity in the UK, particularly in relation to the longstanding Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

As the conversation progresses, it is clear that the remnants of Corbyn’s leadership still resonate within the Labour Party and have become a recurring flashpoint in discussions about antisemitism, freedom of expression, and the future of leftist politics in Britain. The success of Sultana and Corbyn’s new political venture will likely hinge on how they navigate these thorny issues while attempting to galvanize support among an increasingly fragmented electorate. The rejection of the IHRA definition by some leftist factions may either serve as a rallying cry or lead to further alienation from broader public sentiments on antisemitism and the Jewish community.