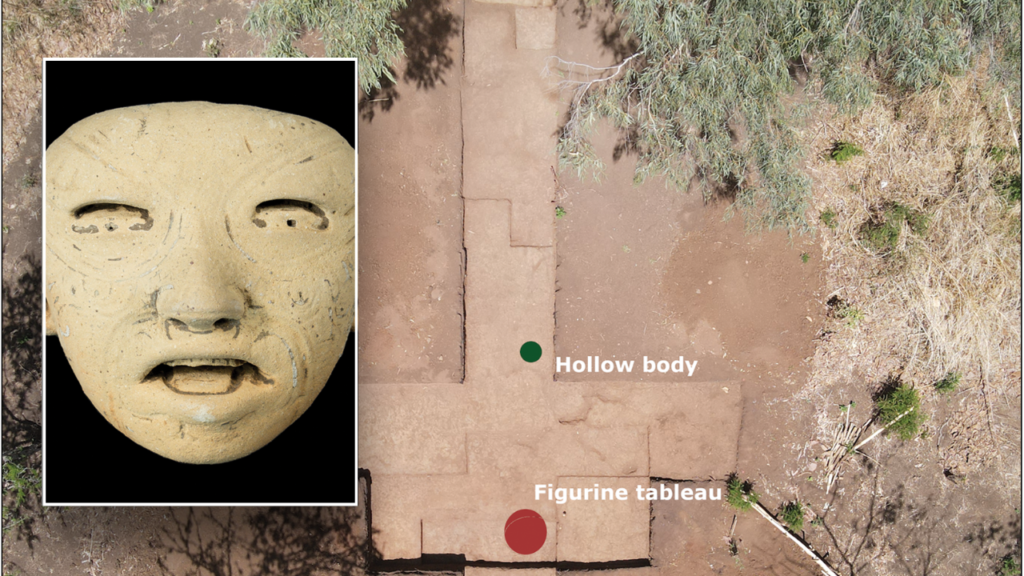

Recent archaeological endeavors in Central America have led to a remarkable discovery: a cache of curious 2,400-year-old clay puppets unearthed atop El Salvador’s San Isidro pyramid. This unexpected find has sparked interest and awe within the archaeological community and beyond, as it reveals insights into the cultural practices of ancient Mesoamerican societies. The findings were officially reported in a scholarly article titled “Of puppets and puppeteers: Preclassic clay figurines from San Isidro, El Salvador,” published on March 5, detailing the significance of these artifacts, which date back to approximately 410 – 380 B.C.

Among the compelling aspects of these puppets are their unsettling, open-mouthed facial features, which appear more vibrant and eerie in person, as noted by Jan Szymański, an archaeologist from the University of Warsaw. Among these ancient figures, the largest measure around a foot in length and are strikingly “naked and devoid of hair or jewelry.” In contrast, the smaller figurines are more intricately designed, showcasing modeled locks of hair on their foreheads and earspools adorning their lobes – details that highlight the artistry involved in their creation.

Researchers have carefully analyzed these artifacts and concluded that the presence of holes in their heads suggests they functioned as puppets. The study elucidates that three of the larger figures possess articulated heads, facilitated by conical protrusions at their necks which allow for an adjustable range of motion. Each head is affixed with a socket that includes holes allowing strings to be passed through to ultimately secure the head atop the body, a mechanism that suggests the puppets could indeed have been used in dynamic performances.

The authors of the study theorize that these clay figures were not merely decorative items but served various roles, potentially acting as marionettes in reenactments of pivotal scenes within their cultural narratives. Though the puppets were found in a state that appeared “naked,” researchers suspect that, much like other discovered figurines from Mesoamerican sites, they were originally adorned with costumes and accessories. Previous findings have unearth earrings and other ornamental elements, suggesting a richer hypothetical background to their ceremonial use.

The discovery of these puppets at such an elevated site presents intriguing implications, with Szymański remarking that their resting place hints at possible ritualistic importance. He expressed the notion that these clay actors were likely employed across various performances and, when no longer needed, were deposited in a manner that connotes significance – almost akin to a tomb, though without the bodies to provide definitive context.

The ongoing excavations at San Isidro remain fruitful, and research into the functions of these puppets continues. In their published conclusions, the archaeologists express hope for further insights to emerge from these findings, particularly regarding the “senders and receivers” of these figures and the relationship they had with the “puppeteers,” who might have taken part in their performances.

The implications of these discoveries extend beyond mere historical curiosity; they encourage a richer understanding of the ancient societal structures that existed in Mesoamerica. This further bolsters the view that culture was interwoven with performance and ritual in ways still relevant to understanding human expression and connectivity today. As excavation efforts at the San Isidro pyramid proceed, researchers remain tenacious in their pursuit of uncovering additional answers that these mysterious clay puppets may hold regarding ancient Mesoamerican life.