In contemporary China, an unusual phenomenon has surfaced among young adults amid a backdrop of significant economic challenges: many are opting to pay for the experience of pretending to have a job rather than facing the reality of unemployment. As the economic landscape falters and the job market becomes more precarious, a growing segment of the youth population has turned to mock occupational environments to simulate the experience of working, seeking community and structure in uncertain times.

The backdrop for this trend is stark. China’s youth unemployment rate has soared past 14%, leaving numerous young individuals feeling despondent and isolated at home without employment prospects. In Dongguan, a city situated just north of Hong Kong, this trend has manifested in the emergence of businesses such as “Pretend To Work Company,” where adults can pay a daily fee to access office facilities designed to mimic real working conditions. One example is 30-year-old Shui Zhou, who turned to this option after his food venture collapsed in 2024. He pays approximately 30 yuan (around $4.20 USD) daily for a desk and companionship, finding solace and community in the office setting.

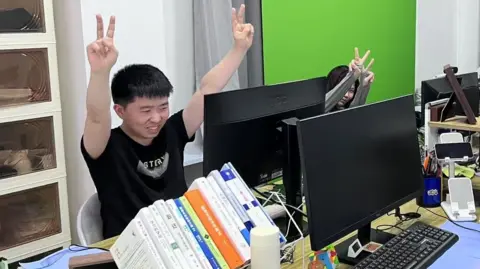

The allure of these simulated workspaces extends beyond merely having a place to go; they are designed to provide a semblance of productivity. Facilities typically include computers, meeting rooms, and even communal spaces for relaxation and social interactions. Participants often use these environments to actively seek employment or develop entrepreneurship ideas, evolving beyond mere pretense. Some facilities even offer perks, such as lunch and snacks, for the entry fee, turning the workspace into a more holistic experience.

Dr. Christian Yao, a senior lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington, notes that these “pretend work” businesses can serve as transitional solutions for many young people caught in the mismatch between educational accomplishments and job availability in the current economic climate. For Shui Zhou, the experience has yielded greater self-discipline and a sense of belonging. He has forged relationships within this community, suggesting that among the attendees, a camaraderie has developed that rivals traditional workplace bonds. His routine has also transitioned towards longer hours, reflecting his commitment to maintaining the appearance of work alongside job hunting.

The phenomenon isn’t confined to Dongguan; cities across China—including Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Chengdu—are witnessing the rise of similar ventures. Young adults like Xiaowen Tang, a university graduate from Shanghai, have utilized such spaces to comply with graduation stipulations requiring proof of employment or internships. Tang cleverly sent images of her time in the “office” to her university as a means of fulfilling these obligations, while simultaneously engaging in creative writing to earn some income. This echo of peer sentiment resonates across the wider youth demographic pushing the narrative that faking it until you make it is a viable coping mechanism in the throes of uncertainty.

Experts have noted that the trend reflects deeper societal frustrations about employment opportunities and economic stability. Dr. Biao Xiang, a director of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, describes this behavior as a coping strategy where the young navigate feelings of being overwhelmed by societal expectations.

Operating a business like the Pretend To Work Company has its complexities. Owner Feiyu—a pseudonym to protect his identity—reveals that he started this venture following a personal experience of job loss during the pandemic. He describes his motivation as providing a sense of direction and dignity to clients who might otherwise feel loss of purpose. Interestingly, 40% of clients are recent graduates, many utilizing the service as a way to appease familial pressure regarding job status.

While the long-term viability of such businesses remains uncertain, Feiyu views his endeavor as a social experiment rather than merely a profitable venture. He hopes to guide clients from a temporary facade of employment to genuine opportunities. The mock workplaces can provide a space where individuals can refine skills—such as those related to artificial intelligence, which Shui Zhou is currently pursuing.

In summary, the occurrence of paying to pretend to work represents a multifaceted response to China’s pressing youth unemployment crisis. This peculiar yet ingenious solution illustrates not just a struggle with economic realities, but also highlights the human need for connection and structure in times of adversity. As young adults navigate their futures in this manner, they not only create a support network but also work towards turning transient roles into meaningful career paths amidst challenging economic conditions.