The rise of wearable technology, particularly smartwatches and fitness trackers, has been transformative in the field of health monitoring. These devices, which can track various metrics such as heart rate, sleep patterns, and activity levels, have become a multi-billion dollar industry. Government officials, like Health Secretary Wes Streeting in the UK, have even suggested that wearables could be provided to millions of NHS patients, enabling remote monitoring of symptoms related to diseases like cancer. Despite the promises of improved health outcomes and personal insights, medical practitioners are expressing considerable caution regarding the reliability and overall usefulness of the data produced by these devices.

One illustrative example comes from an individual trying out the Ultrahuman smart ring, which reportedly provided an alert about an elevated temperature before the user realized they were becoming ill. While this anecdote highlights the potential benefits of wearables, it also raises a critical question: could such data genuinely inform medical professionals about a patient’s condition? For instance, the Oura smart ring allows users to compile their health data into a report that can be shared with doctors. However, not all healthcare providers are convinced of its utility.

Dr. Jake Deutsch, a clinician based in the U.S. who advises Oura, argues that wearable data helps him better understand a patient’s overall health. But he acknowledges that many doctors question its practical application. Dr. Helen Salisbury, a general practitioner in Oxford, indicates a growing concern about patients arriving in her practice armed with data from their devices. She sees a risk that an excessive focus on tracking metrics could foster a culture of hypochondria, where individuals may seek medical attention for benign fluctuations in their health data. This concern is compounded by the reality that many of the anomalies indicated by wearables are often trivial or the result of temporary fluctuations rather than serious health concerns.

The concern extends beyond behavioral implications to the physiological limitations of wearables. Dr. Salisbury points out that many abnormal readings, like a slightly elevated heart rate, can occur due to benign reasons, including device errors. Moreover, wearables can foster an oversimplified view of health; while they provide feedback that may encourage healthier habits, such as walking more or reducing alcohol consumption, they cannot detect more serious conditions like cancer that require comprehensive medical evaluation.

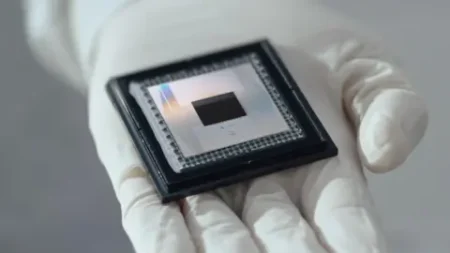

Despite their popularity, the technological limitations of devices like the Apple Watch are also significant. While Apple’s product is heralded as the best-selling smartwatch globally, it is essential to recognize that the technology may not always match the efficacy of conventional medical devices. Clinicians can be skeptical about wearable data, often preferring to rely on their own diagnostic tools. Dr. Yang Wei, an associate professor at Nottingham Trent University specializing in wearable technologies, articulated that while medical monitors used in hospital settings do not face battery life constraints, wearables must constantly balance power consumption with continuous monitoring.

In discussing the inherent inaccuracies that can arise, Dr. Wei explains how movement can introduce ‘noise’ to the data collected by wearables, affecting their reliability. He cautions that while the intention behind wearables is to fill gaps in health monitoring, there’s currently no universal standard guiding how these devices should be produced or how data should be handled. This inconsistency can undermine the potential benefits of integrating wearable data into medical practices.

The interplay between alerts from wearables and medical emergencies was highlighted in a specific incident involving a man named Ben Wood, whose Apple Watch falsely alerted his wife to a supposed crash during a leisurely racetrack visit. His experience underscores the potential for wearables to misinterpret non-emergency situations as critical, illustrating the need for careful management of alert protocols in medical contexts.

Experts such as Pritesh Mistry from the Kings Fund recognize the challenges associated with integrating wearable-generated data into patient care. He suggests that amidst ongoing discussions in the UK, there must be a solid technological infrastructure and support systems in place to fully realize the benefits of wearables in community health settings.

In summary, while wearables hold promise in health monitoring, the medical community remains cautious. Physicians like Dr. Salisbury and Dr. Wei voice understandable concerns regarding the accuracy of data, potential for misinterpretation, and the psychological impacts of an over-obsessive health tracking culture. As the technology continues to advance, the dialogue surrounding its role in healthcare is becoming increasingly critical. Understanding both the opportunities and limitations of wearables is crucial for furthering their integration into patient’s health and wellness strategies.