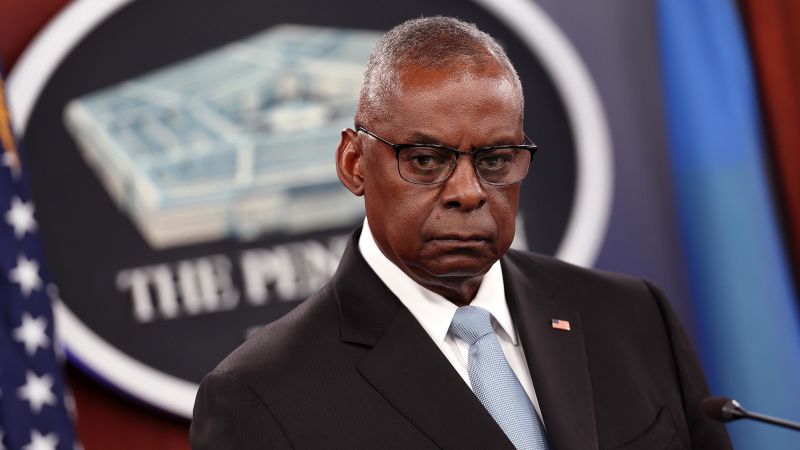

In a significant legal decision, a federal appeals court has affirmed that former Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin had the unmistakable authority to annul longstanding plea agreements with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and two other alleged conspirators of the September 11 terror attacks. This ruling follows a previous determination made by a military judge who deemed these plea agreements—under which the defendants would avoid the death penalty—as “valid and enforceable.” However, Austin’s action to revoke these agreements prior to the military trial has now gained judicial backing, indicating a shift in the handling of these high-profile cases.

The appeals court’s judgment was presented by the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, which stated that “the Secretary of Defense indisputably had legal authority to withdraw from the agreements.” According to the court’s documentation, the straightforward language in the pretrial agreements made it clear that the defendants had not yet commenced the performance of any promises outlined in those deals. Thus, this legal vacuum allowed Austin’s withdrawal from the proceedings without violating any established protocols.

Critics, however, have condemned this ruling as a setback for justice. Wells Dixon, a senior attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights who once advocated for another detainee, Majid Khan, expressed his disappointment with the court’s decision. He articulated concerns that revoking the plea deals would perpetuate “the continued lack of justice and accountability” within the military commission system. Dixon’s words carry substantial weight, particularly given the historical context surrounding the prosecution of 9/11 defendants and the complexities involved in such cases.

He described the Biden administration’s efforts to invalidate the plea agreements as “inexplicable” and labeled them a bitter betrayal for the families of 9/11 victims. For these families, the agony of prolonged litigation without resolution over two decades has fostered skepticism regarding the likelihood of a fair trial that could bring closure. Dixon’s assertion underscores a painful intersection of legal and emotional dimensions as the trials extend indefinitely without a clear resolution in sight.

The ramifications of the military trials have been further complicated by the acknowledgment of the torture that some defendants underwent while held at CIA black sites. Due to the ethical implications and potential admission of evidence regarding torture, the U.S. government finds itself grappling with the admissibility of such evidence in court. Dixon has previously noted that the government appears “unwilling” to confront these issues, which further complicates the prosecution of those accused of planning the devastating 9/11 attacks.

Initially, the pretrial agreements, negotiated over a span of 27 months, aimed to secure guilty pleas from the defendants while sparing their lives from the death penalty. The arrangements necessitated that the accused answer questions from the families of victims, a potentially cathartic process that many families supported—a desire that was met with resistance from factions advocating for capital punishment.

Despite the controversial nature of the plea agreements, which triggered an uproar among some victim advocacy groups, Austin rescinded them shortly after they were made public. His rationale centered on the belief that the decision to accept or reject the agreements should rest exclusively with him, rather than with Brig. Gen. Susan Escallier, the presiding officer of the military courts at Guantanamo Bay. This shift of authority birthed multifaceted legal battles that ensued over months, with defense attorneys arguing that Austin’s actions were not lawful under military regulations.

As legal proceedings progressed, the military judge overseeing the cases, Col. Matthew McCall, ruled that the plea agreements remained legitimate and enforceable, implying that Austin’s timing was flawed. His interpretation suggested that the defendants had initiated procedural steps that bound the agreements.

However, with the latest appeals court ruling on Friday, the prior legal interpretations have been overridden. The DC Circuit Court of Appeals indicated unequivocally that Austin acted within his rights to dissolve the pretrial agreements due to the absence of any performance of obligations by the accused, facilitating his withdrawal without breaching legal frameworks.

In this evolving narrative, the judicial and military responses continue shaping the approach to these significant cases. The implications for 9/11 victims’ families, the accused, and the legal landscape surrounding military commissions remain profound, painting a complex portrait of justice that is far from resolved.