The recent announcement from the government regarding wind energy has made headlines across various media outlets, emphasizing a significant increase in the maximum price that companies generating electricity from new wind farms could be guaranteed. This decision comes as key ministers grapple with the ambitious goals they have set to reduce household energy bills and facilitate a transition towards an electricity grid that is nearly entirely free of fossil fuels by the year 2030.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) made this announcement public in anticipation of the upcoming auction for government-supported contracts. This auction, set to open in August, is crucial, as it represents one of the last windows of opportunity to initiate energy projects that align with the government’s target of Clean Power by 2030.

The Conservatives, the main opposition party, have not shied away from criticizing the new pricing structure, referring to the increased costs for offshore wind as “eye-watering.” They argue that these figures could impose additional burdens on energy consumers. However, the government has clarified that these inflated prices do not necessarily reflect the final guaranteed amounts, as companies will likely submit lower bids to secure contracts once the auction kicks off.

A spokesperson for the Energy Secretary, Ed Miliband, has pointed out that history shows auctions can result in much lower prices than the maximum guarantees. For instance, during auctions from previous years, actual prices often settled significantly below the maximum stipulated figures. This suggests a competitive bidding environment is anticipated and needed to lower overall costs for consumers.

This annual auction mechanism is structured to allow competitive bidding from companies eager to build renewable energy projects. The government guarantees a fixed price for the electricity produced over designated periods, which can now extend up to 20 years, under the framework specified by the Administrative Strike Price (ASP). While firms aim to place bids below this ASP to clinch contracts, the government subsequently determines a new guaranteed clearing price based on these bids.

In the situation where market prices exceed the clearing price, companies are obligated to pay the excess back to energy suppliers. The expectation here is clear: it will lead to lower energy bills for consumers. Conversely, if market prices drop below the guaranteed amount, energy suppliers and customers will pay the difference to the companies fulfilling the contracts.

Outlined in this year’s adjustments, the maximum guaranteed price for offshore wind has risen to £113 per megawatt-hour (MWh), up from £102 in 2024. Furthermore, floating offshore wind, which utilizes new technologies, saw an increase to £271/MWh, marking a rise from £245. Onshore wind prices have seen a milder inflation from £89/MWh to £92/MWh, while solar energy has experienced a decline, now set at £75/MWh, down from £85/MWh.

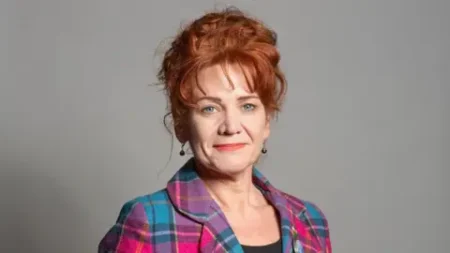

Conservative Shadow Energy Secretary Claire Coutinho described these new figures as the “highest in a decade,” asserting that they are unfairly elevated compared to last year’s average energy costs. She has voiced concerns regarding hidden costs associated with the electricity grid, energy storage, and wastage, claiming that they would ultimately burden consumers further. Coutinho argues that Miliband’s approach prioritizes environmental goals over economic realities and living costs.

In response to criticisms, the government contends that moving towards renewable energy sources will ultimately shield consumers from fluctuating gas prices and provide more stable and lower bills in the long run. This narrative aligns with the broader context of establishing a cleaner energy future.

Johnny Gowdy from the not-for-profit energy advisory group Regen indicated that the newly introduced ASP is primarily a mechanism to establish a competitive starting point for the auction. His observation highlights the intricate balance between bid pricing and project capacity, noting that if higher bids are recorded, the government could end up procuring less capacity, whereas lower bids could facilitate purchasing more.

Historically, previous auctions have yielded clearing prices beneath the established maximums. However, there remains a risk with setting the maximum price too low, which in earlier scenarios led to no bids from offshore wind developers in 2023 due to viability concerns at the established price.

Recognizing the need for reform, the government has made notable changes to this auction system, which includes allowing offshore wind projects without full planning permission to apply for contracts and extending contract lengths from 15 to 20 years. A vital update is that the Energy Secretary will now review developers’ bids prior to finalizing the overall budget.

The overarching message from the DESNZ is clear: the adopted reforms aim to create a competitive auction process capable of securing optimal prices for consumers while ensuring the procurement of necessary clean energy to transition away from fossil fuels.