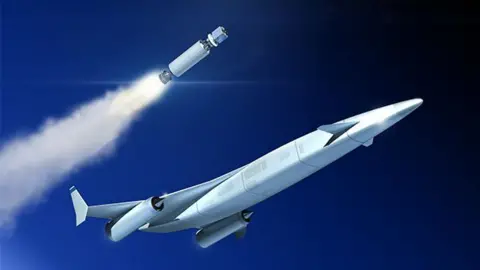

The title “The British Jet Engine That Failed in the ‘Valley of Death'” introduces a tale of innovation, struggle, and the harsh realities of aerospace engineering. Published on June 2, 2025, by Michael Dempsey, a technology reporter, this article recounts the journey of Reaction Engines, a British company that aimed to transform hypersonic flight through its revolutionary engine technology.

At the center of this narrative is Richard Varvill, the former chief technology officer of Reaction Engines, who reflects on the emotional toll when high-tech aspirations crumble. His recounting of the company’s ambitions and failures provides insight into the challenges of developing groundbreaking aerospace technology. Reaction Engines traces its lineage back to the Hotol project of the 1980s, an audacious attempt to create a spaceplane capable of flying beyond the atmosphere.

The crux of the Hotol project lay in its innovative heat exchanger technology, devised to cool the super-heated air entering the engine at hypersonic speeds, which can reach temperatures of around 1,000°C. Varvill emphasizes that without effective cooling, the engine parts would melt—a situation described vividly as “literally too hot to handle.”

Fast-forward to October 2024, Reaction Engines advanced to the stage of implementing its heat exchanger technology in projects across the UK and the US. Support from the UK Ministry of Defence, in partnership with Rolls-Royce, was initially a lifeline, enabling research into potential hypersonic applications. However, this financial backing proved insufficient to sustain the company in the long term. Specifically, Varvill points out that Rolls-Royce ultimately shifted its focus elsewhere, leaving Reaction Engines with limited resources.

As the company neared its operational end, Varvill was acutely aware of the looming financial crisis. The aerospace industry notoriously requires extensive time and investment to bring products from conception to market. This “Valley of Death” in aviation describes the challenging phase where innovative projects struggle to secure the necessary funding to continue. Reaction Engines was in a dire position, desperately seeking financial backing to extend its operations as potential investors hesitated.

The atmosphere in the office during the final days was tense and somber. Varvill recounts an unsettling meeting where the managing director conveyed to the staff that every possible effort had been made to save the company, culminating in the difficult process of collecting personal belongings and passes. The emotional gravity of the moment left many employees in tears, revealing the emotional investment they had in the company’s vision and potential success.

Kathryn Evans, another key figure at Reaction Engines, echoed Varvill’s sentiments. As head of space efforts focusing on hypersonic technology, she too felt the impact of the sudden shift when layoffs were announced, striking her and her colleagues in the auditorium on October 31. Despite her hopes that the company might find a way through the uncertainty, she recollects the moment as traumatic—the suddenness of the news brought an adrenaline crash and the stark realization that years’ worth of effort had reached its end.

In the wake of the collapse, former employees attempted to find closure and celebrate their contributions to what was deemed “British engineering at its best.” Varvill and Evans both reflected on the potential that had been left unrealized, while seeking solace in the possibility that the company’s intellectual property might still find a home in another venture.

Adam Dissel, president of Reaction Engines, who managed its US operations, lamented the missed opportunities for funding, insisting that the innovative technology was ready yet failed to ignite investor enthusiasm. The involvement of prominent industry names like Boeing and BAE Systems might have lent credibility, but they appeared to retreat from providing the necessary support in the end.

As the mournful business winding down commenced—with personnel offboarding and servers prepared for potential salvage—insight was gained into the fragility of pioneering technology ventures. The somber event was marked by a sense of collective loss but also the notion that even amidst failure, the team had achieved significant milestones, grappling with the harsh realities that plagued their aspirations.

Varvill’s poignant conclusion captures the essence of the venture’s failure: “We failed because we ran out of money.” The dedication, innovation, and ambition displayed throughout the years serve as a backdrop to a cautionary tale in high-tech entrepreneurship, traveling through an industry defined by its remarkable yet unforgiving nature.