Paleobiologist Dr. Kenshu Shimada’s lifelong fascination with fossilized sharks, particularly the gargantuan Otodus megalodon, can be traced back to his childhood experiences. At the tender age of thirteen, he unearthed his first megalodon tooth, igniting a passion that would lead him to a career studying ancient aquatic life. However, when he watched the 2018 movie “The Meg,” he realized that Hollywood had taken significant liberties with the creature’s characteristics. Not only did the film portray the megalodon as an existing species in modern times, but it also depicted this prehistoric predator as a massive 75-foot-long (23-meter) behemoth, far exceeding what was previously accepted by researchers.

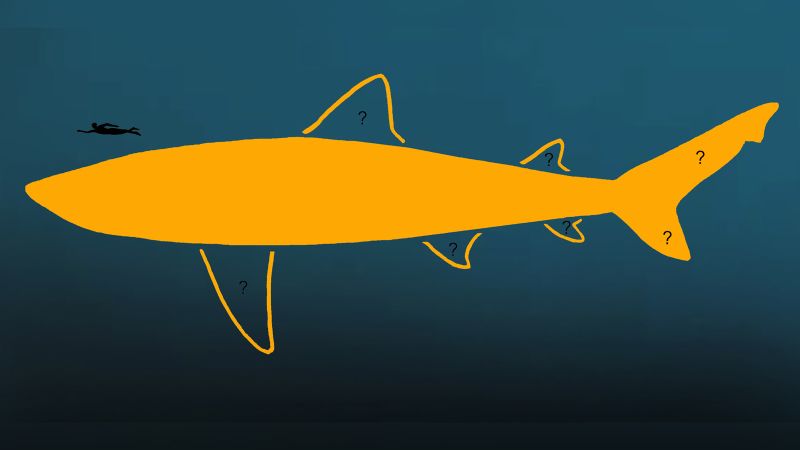

For years, the actual dimensions of megalodon have puzzled scientists because no complete fossil specimens have ever been recovered. However, Dr. Shimada’s recent research indicates that this formidable predator may have reached lengths of up to an astonishing 80 feet (24 meters). This new perspective challenges previously held beliefs regarding the megalodon’s size and shape, suggesting that it was more slender and hydrodynamic than earlier models portrayed. The study published recently in *Palaeontologia Electronica* argues that megalodon bore physical similarities to contemporary sleek sharks, like the lemon shark, rather than being merely a large-scale version of the great white shark.

According to Dr. Shimada, who leads research at DePaul University in Chicago, there is much more to understand about megalodon than simply its monstrous dimensions. He emphasizes the importance of moving away from simplistic comparisons with great white sharks, as this may obscure the unique evolutionary adaptations that megalodon possessed. These findings have potential implications for both scientific understanding and popular culture’s portrayal of this apex ocean predator.

Megalodon was not contemporary with humans; in fact, it ruled the seas between 15 million and 3.6 million years ago, as indicated by various megalodon fossils that scientists have uncovered globally. As a member of the cartilaginous fish family, megalodon’s skeletal structure lacked traditional bones and consisted of a less mineralized composition. In contrast, its teeth remained incredibly robust, resulting in a relative abundance of fossilized teeth that serve as portals into its life.

The fossil record includes not only teeth but also parts of its skeleton. Researchers have retrieved significant samples, such as a 36-foot-long (11-meter) fossilized vertebral column from Belgium, with individual vertebrae measuring up to 6 inches (15 centimeters) in diameter. To illustrate the scale, human vertebrae measure about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) across. The absence of megalodon teeth associated with these vertebrae led scientists to infer their belonging to the same species based on size and morphology.

Interestingly, the earlier assumptions regarding megalodon’s stocky physique were rebuffed during recent investigations. Dr. Shimada and some of his colleagues re-examined prior work that produced a digital 3D model, discovering inconsistencies regarding the shark’s proportions. This prompted Shimada to explore alternative models among modern shark species to find a more accurate representation of megalodon’s physical form.

In conducting comparative research on 145 living shark species and 20 extinct ones, Shimada and his team built a detailed database that analyzed the proportions of various anatomical features. Their calculations led them to propose that megalodon’s most efficient shape resembled a slender, streamlined fish rather than a robust, tanklike predator like the great white shark. This realization raised broader questions about the reasons behind size disparities among marine vertebrates.

Shimada posits that a slimmer body may allow for more significant growth in size while maintaining efficient movement through water. For instance, while great white sharks max out around 20 feet (6 meters), sleek species such as blue whales can expand up to 100 feet (30 meters) without sacrificing agility. This principle directly applies to the newly proposed measurements of megalodon, emphasizing a potential length of 80 feet (24 meters) while also confirming its slimmer physique— a remarkable deviation from earlier theories.

Dr. Stephen Godfrey, a curator at the Calvert Marine Museum in Maryland, expressed surprise at both the suggested resemblance to a lemon shark and the increased estimated size. He acknowledged that while the streamlined body theory holds merit, the increase in length from 50 to 80 feet challenges preconceived notions in the paleontological community.

Ultimately, the only definitive way to ascertain the true size and shape of megalodon rests in the discovery of a complete skeleton, as Dr. Shimada pointed out. Only then can scientists definitively confirm or refute whether this extraordinary predator was indeed the long and sleek creature his research suggests.