The recently implemented UK-French “one-in, one-out” pilot scheme is part of a significant effort to address the ongoing challenge of illegal migration across the English Channel. As the UK government prepares to activate this strategy, which entails the return of migrants arriving in the UK on small boats to France, it is crucial to understand its components and implications on both sides of the Channel.

First and foremost, this new agreement seeks to deter the rising number of illegal crossings by allowing authorities to detain individuals who arrive unlawfully and send them back to France. As part of the arrangement, the UK will accept a corresponding number of asylum seekers from France, provided that these individuals meet certain criteria: they must not have previously attempted the crossing and must successfully pass security and eligibility checks. This exchange aims to maintain a balanced approach to addressing migration while also addressing safety and immigration enforcement.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer characterized this pilot scheme as the product of extensive diplomatic negotiations, highlighting a commitment to developing practical solutions to tackle the issue of small boat crossings. However, the Conservative opposition has voiced skepticism, arguing that the plan will have minimal impact on the migration crisis. Despite differing political views, the urgency surrounding this issue remains undeniable, especially given the alarming statistics of boat crossings recorded earlier this year.

The agreement between Sir Keir Starmer and French President Emmanuel Macron was initially established in July, pending review by the European Commission and EU member states. With approvals now secured, the scheme can move forward. Under its terms, adult migrants attempting unauthorized crossings may face return to France if their asylum claims are deemed inadmissible. Prime Minister Starmer stated that the initiative could see deportations commence within weeks, presenting a significant shift in the UK’s approach to handling illegal entries.

Under international and domestic laws, the UK government cannot repatriate asylum seekers to their home countries before evaluating their claims. However, the arrangement allows for the transfer of these individuals to safe countries that are willing to process their applications. The specifics of how many migrants will be returned or accepted under this pilot scheme remain vague. Still, the government aims to increase the frequency and scale of returns throughout the trial period. Recent reports suggest that the target for returns could be approximately 50 individuals weekly, contrasted with the notably high weekly average of over 800 crossings currently occurring.

The backdrop to this scheme is a marked increase in the number of individuals crossing the Channel in small boats. By July 30, 2025, figures indicated that over 25,000 individuals had made the perilous journey, signifying an almost 49% rise compared to the previous year. This drastic escalation raises significant concerns for the government, which has emphasized its commitment to disrupting the networks of organized crime responsible for facilitating these dangerous crossings.

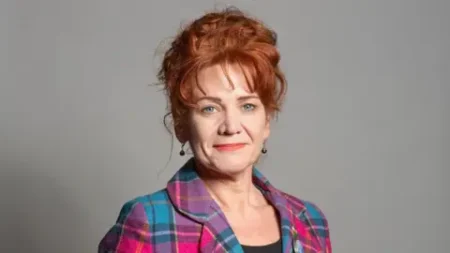

Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has praised the newly established agreement as groundbreaking, signifying an important step in undermining the operations of people-smuggling rings. She emphasized the need for migration to take place through structured and legal channels, rather than dangerous routes. Backing this scheme, the UK government has pledged £100 million to fund the recruitment of 300 officers from the National Crime Agency to combat human trafficking.

Criticism exists concerning the effectiveness of this plan in comparison to previous proposals, particularly a controversial plan involving deportations to Rwanda, put forward by the former Conservative administration. Critics, including members of the Labour Party, have argued that these measures do not sufficiently address the core issues driving individuals to undertake such perilous journeys.

Non-governmental organizations, such as Asylum Matters, assert that the solution to the issue of unsafe crossings lies in creating genuine pathways for asylum seekers to find safety rather than restrictive measures that compel desperate individuals into dangerous situations. Their calls for real safe routes highlight a broader view on how to address the complexities surrounding migration. As the pilot scheme rolls out, it will not only influence the landscape of migration across the Channel but also ignite ongoing debates on the ethics and effectiveness of migration policy in the UK and beyond.