The Song of Wade, a chronicle less renowned than the tales of Gilgamesh, Beowulf, and King Arthur, serves as a poignant example of the consequences that ensue when narratives are not documented. This epic narrative was once a staple of medieval and Renaissance England, so revered that Geoffrey Chaucer alluded to it not once, but twice in his own renowned works. However, today, this saga has largely faded into obscurity, with only fragments of its existence surviving through time. Recent scholarly pursuits have unearthed revelations which demonstrate that, when mere snippets of a narrative remain, alterations in a single term can drastically reshape the entire story.

Originating in the 12th century, the Song of Wade once depicted its titular hero as engaging in battles against mysterious monsters—a concept rooted in traditional interpretations. The primary fragment of this tale emerged almost 130 years ago in a 13th-century Latin sermon that quoted a discerning passage in Middle English. The critical excerpt features the term “ylues,” which was formerly translated as “elves.” This interpretation led scholars to assume the tale was rich with fantasy and supernatural beings, contributing to the image of Wade as an otherworldly hero.

Recent research from the University of Cambridge has challenged these long-held beliefs. According to the new interpretation presented by researchers, the original meaning of “ylues” was distorted due to transcription errors made by a scribe who altered a “w” into a “y.” The term actually refers to dangerous men, with “elves” reverting to “wolves.” Additionally, another term previously thought to refer to “sprites” is better interpreted as “sea snakes,” thereby substantially altering the narrative from one steeped in the mythical realm to one firmly grounded in worldly dangers. This revision has the potential to transform our entire understanding of the Song of Wade, as explained by Dr. Seb Falk, a researcher and coauthor of the study.

Dr. Falk notes that Wade can be reimagined as a chivalric hero—akin to figures such as Sir Lancelot or Sir Gawain. This reinterpretation provides a more coherent fit within the context of Chaucer’s works, particularly those focusing on themes of courtly love and chivalry. There has been extensive debate among historians and literary experts over why Chaucer referenced the Song of Wade in his actions of courtly intrigue, and re-characterizing Wade lends understanding to these references.

The newly published study is a pioneering endeavor, as it simultaneously scrutinizes both the Song of Wade excerpt and the broader Latin sermon from which it is cited. Dr. James Wade, an associate professor at Girton College, highlights that the context of the sermon was crucial to ascertain the true meaning of the fragment—one steeped in humility and caution against tyrannous actions, symbolized through references to “wolves” and other allegorical creatures.

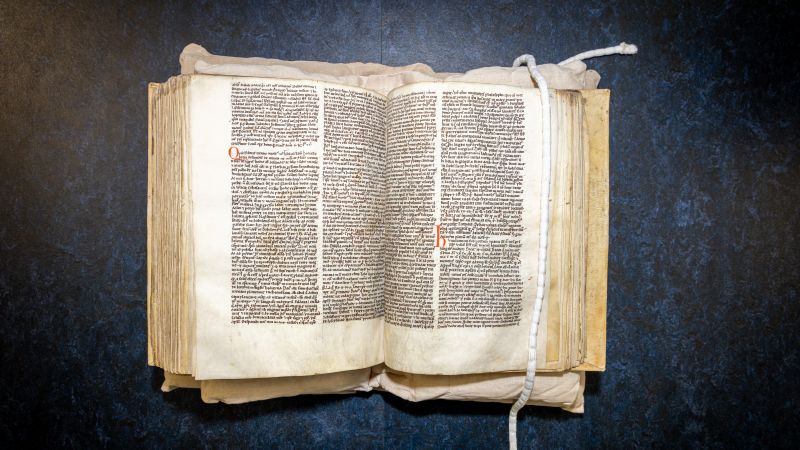

The revelations prompted by this research signify a shift in understanding, emphasizing that stories weren’t just one-dimensional; they were often layered with cultural significance. It emphasizes the pivotal role of paleography, which concerns the study of ancient manuscripts, in appreciating the nuances of medieval literature. This complex field requires a blend of skilled interpretation and contextual analysis, particularly given the limitations of medieval vernaculars, which lacked standardized spelling and grammar.

Dr. Stephanie Trigg from the University of Melbourne underscores the significance of the sermon, noting that its rare references to popular epics of the time offer a glimpse into the cultural currents surrounding medieval society. The unique use of the Song of Wade within the sermon implies that the preacher anticipated that his audience would be familiar with this legendary hero—a common cultural “meme.”

While the newly discovered insights indicate a more realistic view of Wade’s adventures, they do not strip the narrative of fantastical elements entirely. Medieval romantic tales often intertwined realism with elements of folklore and legend, culminating in a narrative style that captured the imagination. For instance, in various references throughout history, Wade is depicted as a dragon slayer and described as a being of gigantic size, with familial ties to giants and mermaids—elements reminiscent of modern epic narratives, such as those crafted by J.R.R. Tolkien.

Despite the myriad elements of fiction and fantasy, correlating the Song of Wade with medieval romance elucidates the confounding allusions made by Chaucer, especially when invoked within the realms of courtly love and social intrigue. Chaucer’s references to Wade carry a deeper significance when understood through this contemporary lens, providing clarity at the intersections of chivalric and mythical narrative forms.

Although the tale of Wade has drifted into the shadows of history, its echoes within the medieval sermon and Chaucer’s poetry suggest it once enjoyed a vibrant existence in the cultural zeitgeist of medieval England. It signifies the ongoing allure of lost stories, tales that once captivated the imagination of society but have since dwindled into obscurity—a phenomenon that ignites curiosity for what such narratives could reveal about human history, culture, and creativity.