Researchers have recently uncovered fascinating insights into the enchanting world of birds-of-paradise, a group renowned for their vivid coloration. While many birds exhibit splendid colors, including the vibrant hues found in hummingbirds, peacocks, and parrots, birds-of-paradise stand out for their extravagant displays, characterized by emerald, lemon, cobalt, and ruby shades. Recent investigations reveal that these birds are not only visually striking but also communicate through secret color signals invisible to the human eye, a discovery that has opened new avenues in the study of avian communication.

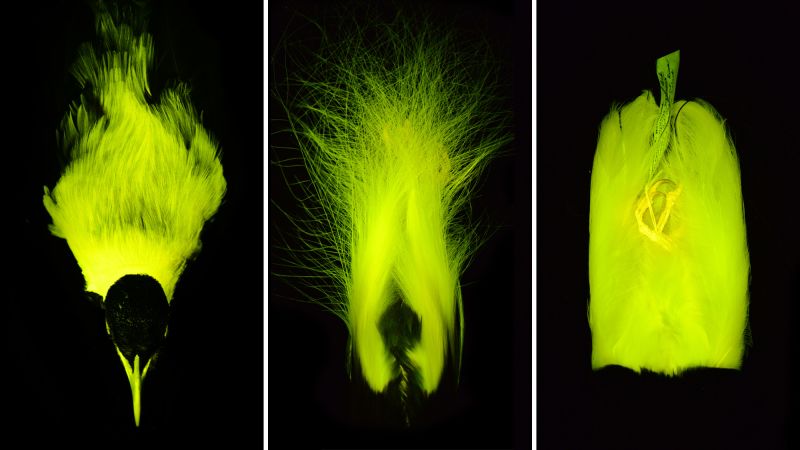

In a study published on February 12 in the respected journal, Royal Society Open Science, scientists demonstrated how the plumage and body parts of birds-of-paradise emit a glow when viewed under blue and ultraviolet (UV) light, manifesting bright green or yellow-green colors. This phenomenon constitutes biofluorescence, a biological process distinct from bioluminescence, such as that exhibited by fireflies, which involves chemical reactions between specific molecules like luciferin and luciferase. Biofluorescent organisms, conversely, absorb high-energy wavelengths (like UV) and re-emit them as lower-energy light.

Remarkably, researchers identified biofluorescent traits in 37 out of the 45 known species of birds-of-paradise, which inhabit isolated tropical forests and woodlands in regions like Papua New Guinea, Eastern Indonesia, and parts of Australia. Under blue and UV light, these birds showcase luminescent plumage patterns that may have implications for territory establishment and mate attraction, offering insight into the evolutionary advantages of such visual signals.

Birds are renowned for having superior visual acuity, including a capacity to perceive UV wavelengths. Though much about birds-of-paradise remains unexplored, other related avian species like crows and ravens have shown sensitivity to violet light wavelengths. Therefore, for these animals, the fluorescent markings emitted by birds-of-paradise could be perceived as vibrant signals in low-light conditions, thus enhancing their communicative capabilities.

Dr. Jennifer Lamb, an associate professor at St. Cloud State University, acknowledges the significance of the study’s approach. She observes that despite biofluorescence being a potential visual signal among numerous animal groupings, it remains an underexplored domain, often overlooked because it exists beyond human visual perception. This highlights a broader gap in understanding how various animals communicate visually.

Notably, the study’s lead author, Dr. Rene Martin, pointed out that while birds-of-paradise are celebrated for their dramatic coloration, the biofluorescent aspect of their signaling system has remained largely undocumented until now. She insists that this discovery is an essential piece of the broader puzzle of avian communication, emphasizing the potential for similar findings across other well-explored groups.

The curiosity behind the occurrence of biofluorescence in birds-of-paradise extends to other animal groups. Dr. John Sparks, a curator at the American Museum of Natural History, first identified biofluorescence in numerous fish species over a decade ago, nurturing questions about how extensively this trait may exist in the animal kingdom. Utilizing comprehensive specimens at the museum, Sparks confirmed the presence of fluorescent indicators within the birds-of-paradise during a preliminary investigation.

Martin’s deeper exploration began upon joining the museum as a postdoctoral researcher in 2023. Together with co-authors, including doctoral student Emily Carr, she conducted thorough assessments of the ornithology collection using specialized blue and UV flashlights to expose the fluorescing attributes of these displays while employing goggles to filter out ambient light.

The latest research found that the fluorescent phenomena varied across different species, illuminating various bodily areas, including bellies, necks, and even inside the birds’ mouths. Often, these fluorescent regions were bordered by ultra-dark feathers, enhancing the visibility of the glow.

Despite over 11,000 recognized bird species, biofluorescence appears restricted to only a select few. Apart from birds-of-paradise, similar properties have been documented in auks, owls, and parrots, but the functionalities behind these signals remain largely ambiguous. Martin speculates that while some species likely use fluorescence for communication or mating displays, other instances might remain purely coincidental.

As research continues to unravel the capabilities of biofluorescent species, scientists have noted its manifestation across numerous taxa, including fish, mammals, and reptiles. Understanding this extensive evolutionary characteristic enriches knowledge about animal communication and has implications for medical and technological advancements, as observed in applications of fluorescent proteins discovered in jellyfish.

Ultimately, the exploration of biofluorescence offers profound insights into the intricacies of animal behavior and communication. As Dr. Martin aptly indicates, the presence and significance of biofluorescence across various life forms vividly underlines the myriad ways organisms adapt and evolve to thrive in their environments.