In a significant policy shift that has raised alarm among humanitarian organizations and development advocates, the UK government has announced cuts to its foreign aid budget, particularly impacting African nations. This announcement was articulated in light of a broader effort to reallocate funds, with foreign aid spending slated to decrease from 0.5% of the gross national income to 0.3%. The government claims this action will enable an increase in defense spending, particularly in response to escalating pressures from the United States.

The specifics of the reductions indicate that support for crucial initiatives, such as education for children and health services for women in Africa, will face the most severe cuts. A recent report released by the Foreign Office outlines these details, clarifying that decreased funding for women’s health and water sanitation programs may lead to heightened risks of diseases and mortality in affected regions. Critics of the government’s decision assert that such cuts will exacerbate the plight of some of the world’s most vulnerable populations.

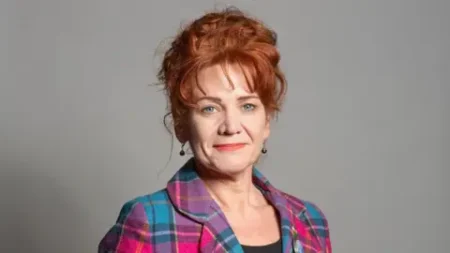

Notably, while the cuts predominantly affect bilateral aid—money sent directly to recipient countries—the government has announced that funding for certain multilateral organizations like the World Bank and the Gavi vaccine alliance will be maintained. This suggests a prioritization of funding through international bodies rather than direct assistance, which has historically been crucial for many affected communities. Baroness Chapman, the minister for development, emphasized a need for better efficiency with taxpayers’ money and mentioned an ongoing strategic review aimed at identifying effective prioritization within the aid budget.

The decision, however, has faced backlash from various quarters. Sarah Champion, chair of the International Development Committee, has voiced her concerns that the cuts will largely harm the very individuals they claim to help—especially vulnerable populations in less developed nations. Furthermore, Bond, a collaborative network for international development organizations in the UK, has highlighted that funding for education, gender equality initiatives, and crisis response in countries like South Sudan and Ethiopia will be de-emphasized.

Concerns have also been raised regarding the implications of these cuts. Gideon Rabinowitz, Bond’s policy director, argued that women and marginalized communities are poised to suffer the most due to these budgetary choices. Rabinowitz expressed that the UK’s commitment to international aid should not only focus on cutting funding but also on addressing the root causes of global challenges, especially during times when other major powers are dampening their support for gender-focused programs.

UNICEF has echoed similar sentiments, stating that the reductions could drastically impact children and women, exacerbating existing inequalities. Philip Goodwin, the chief executive of UNICEF UK, has called for the government to reorient its approach to prioritize initiatives that focus on the well-being of vulnerable children and their families, arguing that at least 25% of the aid should be directed towards child-focused programs.

The outcomes of these cuts pose severe ramifications for existing programs in countries like Sierra Leone, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—nations where UK-funded initiatives have been vital for educational access and health services. Street Child, a British charity, has conveyed its disappointment, asserting that the cuts represent a tragic setback for educational opportunities in regions that are already underserved.

Aid spending in the UK is a politically contentious issue, with rising skepticism and scrutiny from the public, which has been manipulated by various factions within the government. Although the Labour administrations led by Sir Tony Blair and Gordon Brown had pledged to increase foreign aid, recent years have seen a determined pivot towards reducing expenditure in this sector, framing it as a responsibility towards domestic concerns.

As the international development landscape navigates these obstacles, it is increasingly evident that the balance between national interests and humanitarian commitments is delicate. The cuts, while rationalized as a necessary political maneuver, could potentially dismantle years of progress in addressing critical problems such as poverty, education inequality, and healthcare access across some of the world’s most challenging environments. Ultimately, the long-term consequences of this strategy will continue to unfold, and the impact on the most vulnerable should remain a priority in future discussions surrounding foreign aid.