The landscape of clinical trials is a crucial aspect of modern medical research, driving advancements in treatment and healthcare practices. The historical roots of this practice can be traced back to the first controlled clinical trial in 1747, carried out by Royal Navy surgeon James Lind to test treatments for scurvy. Recent research suggests that Lind may have been inspired by the work of Francis Hauksbee the Younger, who laid out a systematic approach to executing a controlled trial just a few years prior to Lind’s groundbreaking work.

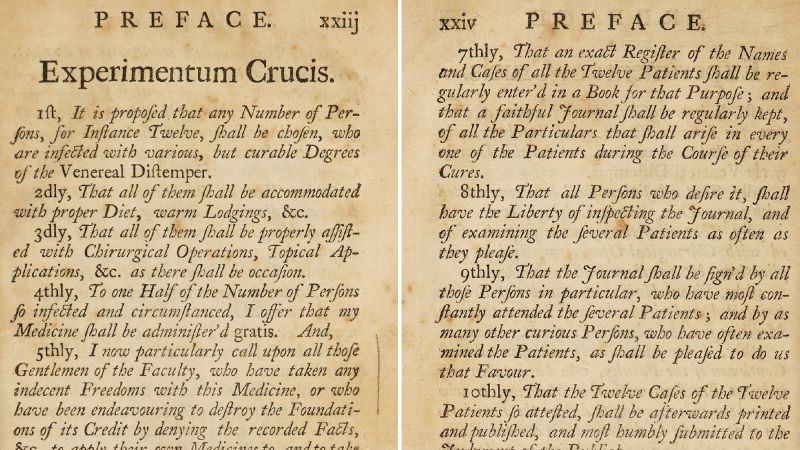

The study conducted by Lind is often highlighted for identifying the effectiveness of oranges and lemons as a treatment for scurvy, a condition that plagued sailors for centuries. However, Hauksbee’s contribution, although lesser-known, marked a shift in the methodology of clinical studies, promoting a more rigorous examination of medical treatments. An analysis of Hauksbee’s trial proposal, published in 1743, reveals that it consisted of a ten-step approach, which anticipated many principles that would come to characterize modern clinical trials.

Hauksbee’s proposal aimed for a systematic comparison of different drug treatments for the then termed venereal disease, including his own medication. He devised a plan involving twelve patients, a model that mirrors Lind’s own study design. Importantly, Hauksbee sought a fair evaluation of each treatment’s efficacy by maintaining a controlled environment for the experiment, as seen in Lind’s assessment aboard the Royal Navy ship HMS Salisbury, where all patients were subjected to similar diets and conditions.

The findings from Hauksbee’s purported study are significant not only in their methodology but also in their spirit of inquiry, as highlighted by lead study author’s reflections on the scientific rigor demanded by Hauksbee. He called for evidence supporting his treatment as well as evidence opposing it, reflecting a departure from the era’s common medical practices, which often lacked empirical evaluation. This openness to scrutiny was indeed quite progressive for a medical researcher at the time, especially considering that many physicians of the 18th century claimed their practices could cure a wide array of illnesses, often disregarding their potential side effects.

It’s important to note that Hauksbee was not a physician, which significantly hindered the acceptance of his ideas within London’s medical community. Instead, he was labeled a “quack” by his contemporaries, reflecting the prevailing attitudes toward non-licensed healers. The stigma attached to those without formal medical training diverged sharply from the scientific exploration that individuals like Hauksbee sought to promote. His pamphlet outlining the trial proposal came shortly after a notable parliamentary investigation into a medical treatment involving another non-licensed healer, showing a growing public interest in the efficacy of treatments based on evidence.

While there is no concrete evidence that Hauksbee’s proposed trial was ever conducted, his study design demonstrated a formative understanding of clinical comparison, paralleling the established practice today where a treatment is juxtaposed against a control or alternative. His work, alongside Lind’s, signifies a gradual acceptance of more empirical methodologies in evaluatingtherapeutic interventions, which forms the bedrock of current medical research.

Moreover, both Lind and Hauksbee’s studies considered the patients’ diets and living conditions, illustrating an early recognition of the multifaceted nature of health treatments, an element crucial to modern medical evaluations. As the field of medical research evolved, such comparisons became essential in establishing robust evidence for treatment effectiveness.

Dr. Max Cooper, alongside other scholars, believes understanding these foundational figures in clinical research not only enhances our appreciation of medical history but also provides valuable lessons for today’s medical trainees. By reflecting on past treatments, including those proposed by Hauksbee, future physicians can gain insights into the evolution of research practices and the significance of rigorous trial designs.

In conclusion, the historical study led by Lind reflects a pivotal moment in the evolution of clinical trials, but the groundwork laid by earlier figures like Hauksbee is equally important. His emphasis on methodical treatment comparisons not only contributed to medical science at the time but also resonates within modern research ethos. The acknowledgment of these past figures enriches our understanding of scientific inquiry and illustrates the foundations upon which contemporary clinical practices stand.