In a groundbreaking revelation made in 2023, scientists in Norway have unearthed the world’s oldest dated rune stone, a remarkable piece of history that is part of a nearly 2,000-year-old slab. This monumental discovery, while already significant, has opened up a range of inquiries as researchers aim to reassemble the ancient stone and decode the enigmatic runic writing inscribed upon it. This venture is necessary as it not only aims to uncover who crafted these mysterious characters but also what they signify in the context of early Germanic culture.

According to the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History, runes represented the initial form of Germanic writing, emerging soon after the birth of the first few centuries AD. This fascinating script continued to be utilized in Scandinavia until the late Middle Ages. Researchers believe that the Germanic peoples were inspired by the Roman alphabet when conceptualizing these characters, although the precise origins of runes and their various applications have largely remained obscure. The historical context of runes has puzzled scholars, particularly given the rarity of early examples beyond the Viking Age, which spanned from AD 800 to 1050.

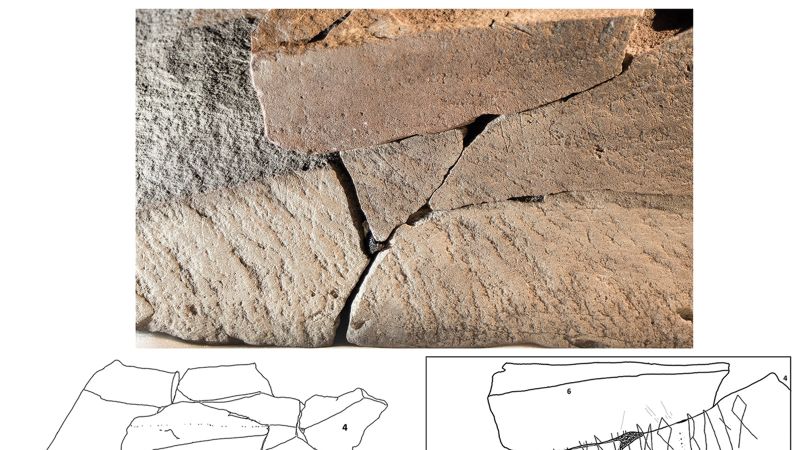

The uncovering of the oldest known rune stone can be traced back to 2021 when archaeologists excavated it while investigating a grave site in eastern Norway. The initial find revealed a sizable fragment covered with runic inscriptions. As the excavation continued, additional sandstone pieces were discovered in adjacent graves, many of which displayed similar markings. This led researchers to theorize that these fragments were once part of a singular stone, as some inscriptions appeared to flow seamlessly from one piece to another.

Intriguingly, the manner in which the stone was fragmented suggests intentionality, indicating that individual pieces were deliberately placed in various burial sites after the stone was broken. Rune stones historically served as memorials or meant to commemorate significant events, and this particular stone’s function appears to have evolved over time. The fragments were ultimately buried alongside cremated human remains, which established them as the earliest rune stone fragments ever documented. Radiocarbon dating has suggested that these pieces date back rigorously between 50 BC and 275 AD.

Dr. Kristel Zilmer, a professor of runology at the University of Oslo, emphasizes the significance of these findings. According to her, the inscribed fragments challenge the previous understanding of the early uses of runic inscriptions on stones. They also offer an unparalleled insight into various inscriptions and different markings that have yet to be cataloged on rune-inscribed stones. This opens up new areas for exploration surrounding the identities of those who carved the runes and their evolving cultural significance.

The fragments have introduced an additional layer of complexity due to the not completely understood runic markings, which pose difficulties in translation. Researchers have found earlier inscriptions on a variety of everyday objects, such as bone combs and iron knives, but translating these runes remains challenging due to the evolving nature of the Germanic languages over centuries.

Dr. Zilmer has pointed out that these rune stones likely possessed both ceremonial and practical intentions. The grave field, alongside the original stone, reflects a intent to commemorate while the later utilization within distinct burials suggests a switch to pragmatic and symbolic purposes. The research team conducted their investigation at Svingerud grave field, located in Hole municipality, roughly 25 miles northwest of Oslo, as a part of rescue excavations necessitated by the construction of new transportation infrastructures.

The inscriptions found at the Svingerud site are particularly intriguing, reflecting a combination of deliberate writing, incomplete attempts, and decorative motifs that embellish the site. One particularly notable inscription includes a name, Idiberug, speculated to be a female name. Alongside this, the clearest inscription fits the mold of a signature from the inscriber, indicating a deeper personal connection to the stone’s purpose and meaning.

However, Dr. Lisbeth Imer from the National Museum of Denmark, while not part of the research team, suggests that the complexities of the findings will challenge existing perceptions of rune stones as mere monuments. The Svingerud stone’s layered history of carving, destruction, and renaming indicates a fluid cultural evolution worthy of further exploration. Such findings not only underscore the importance of proper archaeological excavation during construction but also herald the potential to redefine the narrative surrounding early Germanic culture and their writing systems.

Ultimately, the findings at Svingerud could hold sway over the broader understanding of rune stones in historical contexts, as researchers grapple with both their origins and their evolved significances in the human story that they narrate.