Recent research has significantly deepened our understanding of human brain aging, revealing various lifestyle factors that contribute to healthier cognitive aging. Activities such as regular exercise, avoiding tobacco, and engaging in intellectually stimulating tasks—like learning a second language or playing a musical instrument—are associated with better cognitive health in older adults. These insights come from a review published in the journal Genomic Psychiatry, which analyzed data to understand the multifaceted elements influencing brain health as we age.

One noteworthy aspect of the study indicated that some cognitive abilities observed in older adults may be traced back to test scores obtained during childhood, particularly around age 11. This connection was established through investigations into the Lothian Birth Cohorts, which comprise two groups of individuals born in Scotland in 1921 and 1936. The findings suggest that roughly half of the variations in cognitive decline observed later in life may have roots in childhood cognitive performance.

While childhood cognitive abilities play a crucial role, certain aspects of adult life also appear to exert a positive influence on cognitive function. Researchers found that maintaining mental and physical activity, minimizing vascular risk factors like high blood pressure, cholesterol, and BMI, and speaking multiple languages were linked to improved cognitive performance and slower rates of brain aging. Simon Cox, a co-author of the paper and the director of the Lothian Birth Cohort Studies at the University of Edinburgh, emphasized that no singular lifestyle change acts as a “magic bullet.” Instead, a combination of factors contributes gradually to cognitive health, encapsulated in the notion of “Marginal Gains, Not Magic Bullet.”

Cox and his team found that collectively, lifestyle factors could explain around 20% of the differences observed in cognitive decline among individuals aged 70 to 82. This highlights a significant interplay between various lifestyle choices and cognitive longevity. Through the Lothian Birth Cohorts, researchers conducted extensive cognitive tests as participants aged, starting from age eleven to later years in their seventies, eighties, and nineties.

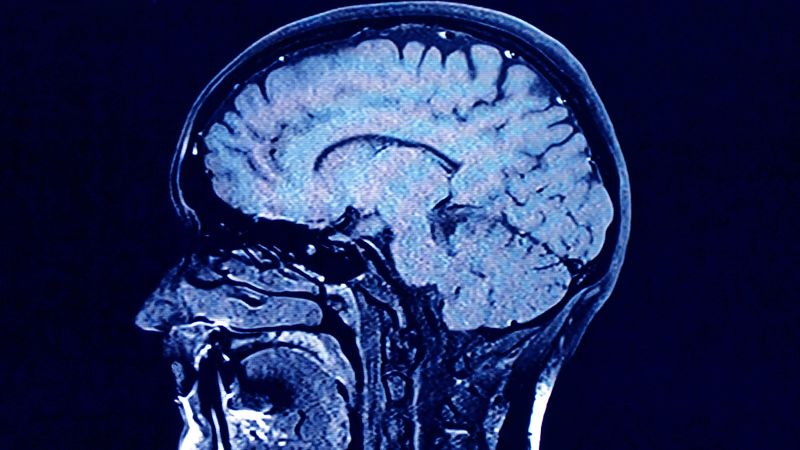

Neuroimaging techniques, particularly MRI scans conducted when participants were 73, unveiled surprising disparities among individuals of the same age. Some scans revealed healthy brains resembling those of individuals 30 to 40 years younger, while others displayed shrinkage and signs of damage typically associated with cognitive decline and dementia. These findings illustrate the diversity of brain aging experiences; decreasing white matter can lead to slower information processing in the brain, emphasizing that aging doesn’t equate to inevitable cognitive decline.

Cognitive “super agers,” older adults whose memory capabilities rival those of much younger individuals, have emerged as a focus within this field of research. Cox noted that not all brain aging features manifest uniformly; thus, understanding how varying risk factors interact is crucial for future studies.

The academic community recognizes that underlying challenges exist in this area of research. Dr. Richard Isaacson, a prominent figure in the study of neurodegenerative diseases, commended the paper for its clear depiction of the trials associated with long-term research and the best practices essential for retaining study value. He highlighted key lifestyle differences that affect the aging brain, including the importance of sleep, as well as the serious impact of mental health conditions like depression on dementia onset.

Complementary to this state of research, lifestyle changes have garnered attention as viable strategies for enhancing brain health. Studies have shown that moderate regular exercises, such as walking and cycling, can substantially boost cognitive abilities, while adherence to a heart-healthy diet can mitigate brain aging risks. Meditation has also demonstrated the potential to positively influence cognitive health.

In addition to these findings, researchers have developed a tool dubbed the Brain Care Score, which assesses an individual’s risk for cognitive decline and cerebrovascular incidents. This 21-point scoring system evaluates various health-related aspects, including blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol levels, body mass index, nutrition, lifestyle habits, sleep quality, stress levels, social connections, and an individual’s sense of purpose in life.

For anyone keen on bolstering their cognitive health, regular medical visits—ideally annually or biannually—are advised. Monitoring key health markers like blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol is crucial. Moreover, maintaining awareness of bone health and muscle strength is vital since these factors correlate strongly with long-term brain health outcomes. In summary, while aging is inevitable, the pursuit of a holistic and proactive approach toward lifestyle choices can significantly improve cognitive aging outcomes.